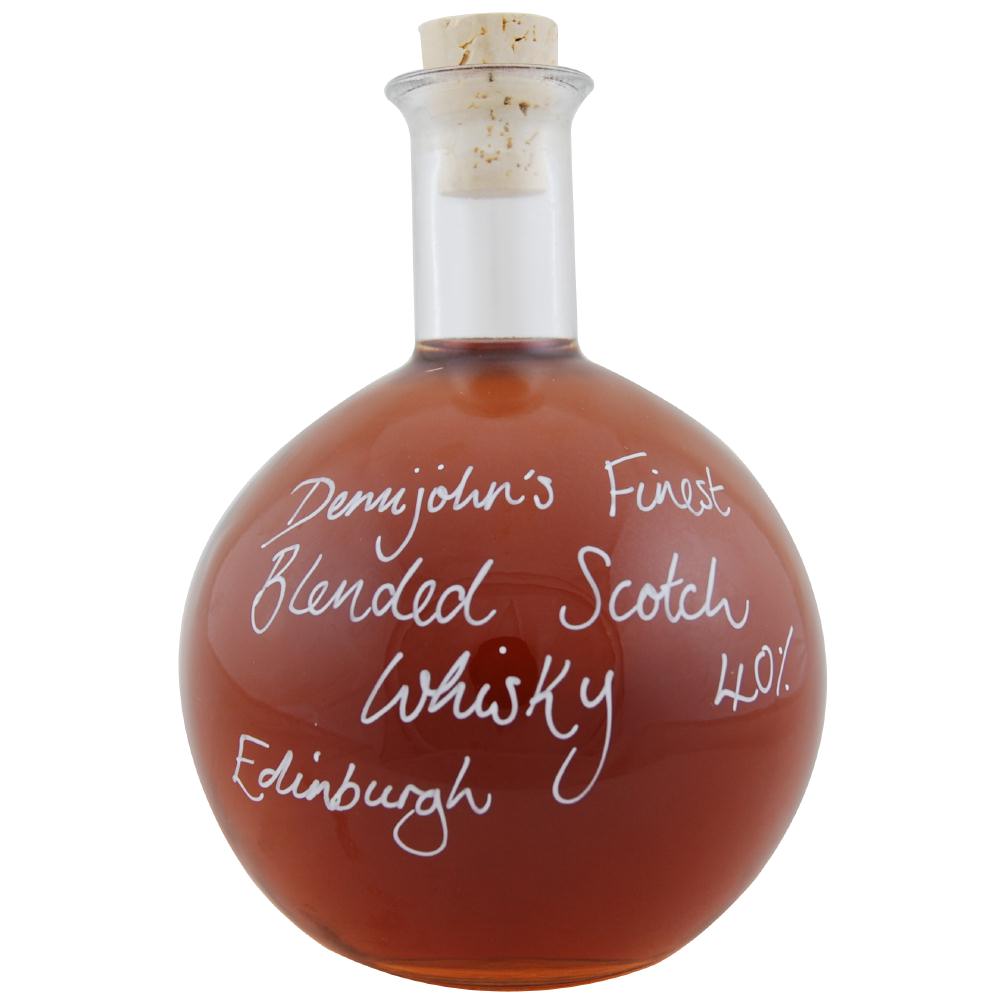

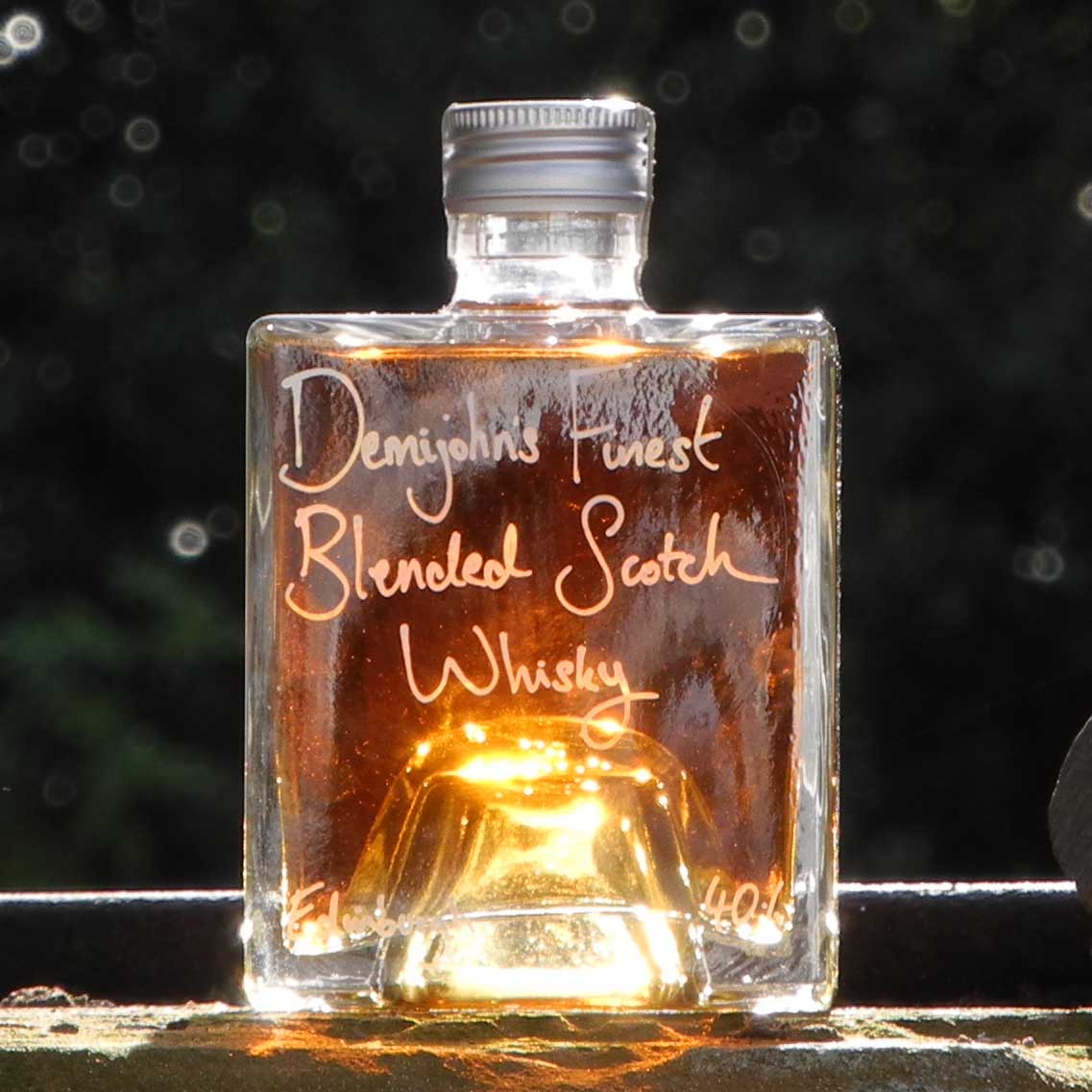

This whisky has been specially blended for Demijohn by Adelphi. The aroma presents an interesting meeting of north-east and south -west characteristics; Speyside pear drops and Islay peat smoke.

What is it like to sniff and sip?

The taste in the mouth is quite remarkably smooth, gentle and well balanced. The tip of the tongue detects traces of salt suggesting Campbeltown or Skye; a trace of walnuts; the sweet dry balance is well contrived and prevents the whisky cloying; the finish is satisfyingly extenuated. Overall impression is full bodied and civilised; ideal for evening, even post prandial drinking.

Anything else I should know?

Blended for us by Adelphi Distillery this delicious blend contains a little of our much loved Caol Ila Single Malt, balanced against a couple of Speyside Single Malts, including Linkwood Single Malt Whisky.

Any more interesting things?

Blended Whisky is created from a mixture traditionally of about 40% single malt whisky mixed with 60% grain whisky.

How is Scotch Whisky made?

In the production of Malt Scotch Whisky the basic raw materials are limited and consist of barley, water and yeast. The process comprises five distinct stages:

-

MALTING which converts barley to malt. In which the barley is first soaked for between 48 and 72 hours in tanks or 'steeps' and allowed to germinate. The germinating barley converts its store of starches into sugars. Germination releases heat which has to be controlled in order to keep the temperature around 60°F/16°C and avoid the barley killing itself from its own generated heat. Traditionally the malting barley was drained and spread out in a layer 30 cm or so thick over a large floor then turned regularly by hand for about a week with rakes or shovels. More recent maltings designs employed either mechanical rakes or large revolving drums to achieve the same effect. A secondary effect of the raking is to prevent the germinating roots from tangling with each other. Green Malt is the term used to describe the germinated barley. It is still alive so must be kiln-dried to stop the germination process. The fully germinated malt is transferred to the kiln for drying on an iron mesh screen over a fire containing a certain amount of peat, thus contributing to the peaty taste evident in many malt whiskies. The malt is dried and roasted in the peat reek at 60°C for two days and is then ready for dressing and milling. There may be several malt bins as distilleries will try and build up a large supply. This holds the dried, peated malt prior to dressing. Certainly distilleries used to have to accumulate enough barley after the harvest to last them through the next distilling year. The malt contains much detritus or 'combings', principally rootlets. These are removed and used as cattle food. The malt is coarsely ground and becomes known as 'malt grist'.

-

MASHING is the next stage which produces wort (sugar solution) from ground or crushed malt. The quality and nature of the water used is absolutely vital to the final product. Water can make or break a distillery and all distilleries guard their water supplies jealously to the point in some cases of purchasing the entire hillside to ensure the supply is not compromised. The malt grist is fed into the 'mash tun' where it is combined with a carefully measured quantity of hot water at around 65°C. This completes the conversion of dextrin into maltose and produces a fermentable solution of the malt sugars called 'wort' or 'worts'. Mash Tuns contain rotating paddles which keep the wort in constant motion. Several washings draw out the malt. The worts are filtered off through a screen and the now spent barley grains into a receiver called an 'underback'. The worts must be cooled to around 23°C to prevent unwanted decomposition of the maltose and to allow yeast to be introduced. FERMENTATION produces wash (a weak, crude, impure spirit) consequent upon the introduction of yeast in the wort. Yeast is added to the cooled worts at which point it becomes known as 'wash'. Thirty-six hours or thereabouts of sometimes violent fermentation produces a weakly alcoholic clear liquid 'wash', which will now be distilled. Fermentation can be extremely vigorous, producing a 'head' several feet deep. Washbacks are often mechanically agitated to knock back the head or it would overflow. The wash is allowed to ferment to a beer-like liquid containing about 5% alcohol.

-

DISTILLATION strengthens and purifies the spirit contained in the wash and also separates the solids contained in the spirituous liquor. The wash is first distilled in the 'wash still' to produce an impure intermediate product called 'low wines'. This is then fed via the spirit safe into the low wines charger ready for the next stage of distillation. When ready, the low wines are discharged into the low wines still and the process repeated. The final product - raw, unmatured whisky passes via the spirit safe to spirit receiver and spirit store, ready for filling into barrels. The spirit safe is a heavy glass-fronted and padlocked box in which the emerging distillate may be inspected and directed onwards or back for redistillation as appropriate. The 'safes' used for spirit storage are exactly that. The moment the intermediate product contains alcohol it comes under the control of the Excisemen and the safes are a necessary means of ensuring that the spirits stay where they are supposed to be and are accurately accounted-for.

-

MATURATION transforms the raw spirit into Whisky. Casks are critical to the taste and appearance of the final whisky. The need is for casks which will impart a characteristic taste to the whisky without dominating it or imparting a 'woody' flavour. Principally two types of cask are used - Oloroso sherry casks and American oak Bourbon casks. Some distilleries use intact barrels, others remake barrels from selected staves from more than one source. The barrel may be charred before use, a process which apparently assists the release of vanillin from the wood. No two casks are the same - one may produce a fine whisky and may be refilled and used again whereas its neighbour may taste woody after one filling. The whisky is left a minimum of three years but usually between 8 and 25 years in wooden barrels to mature. The bonded warehouses are cool and earth-floored to provide an even temperature and humidity. The barrels lose about 2% alcohol per annum - the so-called 'angel's share'.